originally published in 1925

I love the Christmas tree, its unmistakable smell, the kindled magic it brings to the dark days of winter. And yet, this year, I faced a moral quandary: having just written about trees as persons, could I justify bringing a cut tree into my home?

To answer this question, I decided to research the history of Christmas trees. What I learned took me down a curious path, back to the forest of my childhood and that of my ancestors.

Christmas trees are originally a Germanic tradition. The earliest documents we have that reference them are found in Alsace, that long fought-over territory that now belongs to France.

In 1604, a citizen of Strasbourg wrote:

On Christmas they put fir trees in the rooms in Strasbourg, they hang red roses cut from manycolored paper, apples, offerings, gold tinsel, sugar.

In Sélestat, a town in the South of Alsace, there’s an inscription, from 1521, about the guards who had to keep an eye on the local forest where people would cut down trees. Another document from 1611, in Turckheim, sets the fine for anyone caught taking trees.

It would seem that the business of Christmas trees has been controversial from its inception. This isn’t terribly surprising, if you consider that Christmas itself, a culturally-hybrid creature, has long been fraught with religious and cultural tensions.

On a walk in my neighborhood this December, I passed a house that had a sign posted in the front yard: “Keep the Christ in Christmas” it preached. Good luck, I thought, the church has been waging this battle ever since the holiday began!

You’re probably aware that the origins of Christmas are not strictly religious. Although we don’t know exactly how the holiday came to be, historians tend to agree that it combines three cultural influences: Roman pagan, folk pagan and Christian.

December 25th was the winter solstice in the Julian calendar and Romans celebrated it as the birthday of the unconquered Sun. We don’t know for sure that early Christians decided to adopt this holiday for the birth of their savior but it seems logical that they would have chosen to supplant the pagan deity with the “Sun of Righteousness.”

Across Europe, the winter solstice was a significant moment in the year. Even today, we feel the impact of the shortest days of the year. One can imagine what it was like long before electricity, when people’s very survival was tethered to the annual regreening of the world.

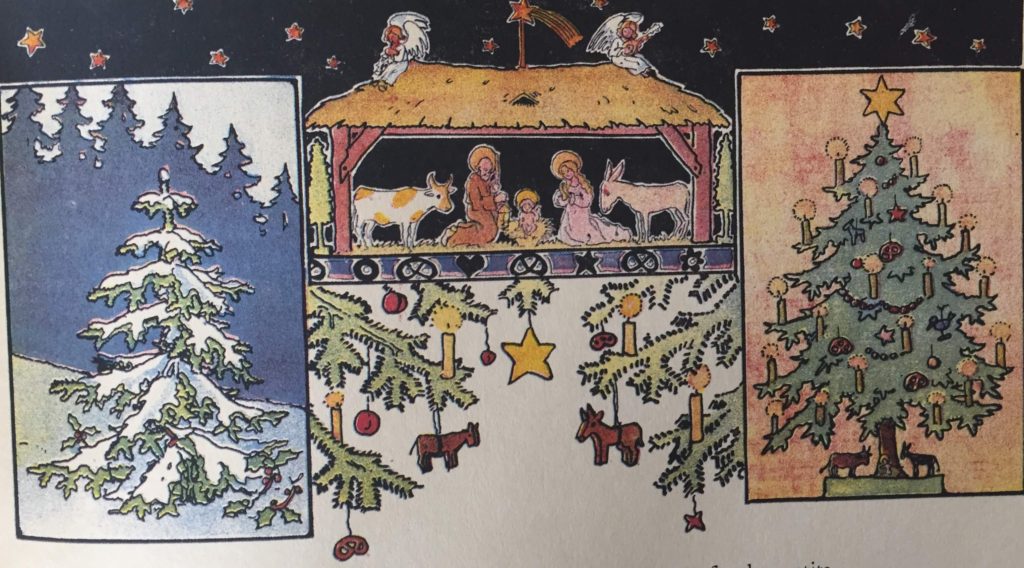

In folk traditions, the days leading up to the winter solstice were felt as the most tenuous time of the year, a time when witches roamed and one had to guard against evil spirits. People sought to bring light and life into their homes, carrying branches and sometimes whole trees inside as a form of protection. They believed that the life embodied by these plants warded off evil influences, as did the candles that eventually adorned Christmas trees.

Bringing plants into the home in the dead of winter also spoke to the promise of renewed life. In Alsace and other parts of Europe, people cut branches from fruiting trees – cherry, plum and apple – in early December and put them in vases. If they flowered by Christmas time, it augured a good harvest. This was a way of celebrating the renewal of life that comes after the solstice and ensuring the bond between human and non-human life.

At the time of year when most plants appear dead to the human eye, it was important to celebrate the dormant life that would bring food and survival. The Christmas tree descends from this tradition and is itself a symbol of fertility. The red and gold-ball ornaments that we still hang on our Christmas trees today recall the apples that were once used, a reference perhaps to a popular belief that pine, apple and other trees bore fruit on Christmas Eve.

In addition to representing the importance of plant survival and renewal in agriculture, the Christmas tree hearkens to the forest itself, that mysterious realm where plant life holds dominion. It recalls ancient cultural traditions in which the tree stood for the cosmos itself. The Christmas tree can thus be seen not only as a representation of our dependence on plant life but as the embodiment of life beyond the human. It certainly recalls for me everything that is mysterious and sacred about the forest.

For the forest has always been an important place to me, perhaps the place. The locus that imprinted itself on me in my childhood, more than any other, was, curiously enough, that same forest where some of the earliest Christmas trees were likely pilfered.

I have mentioned that I was born in Switzerland and that I had an itinerant childhood. But there was one place that was constant throughout my childhood. I spent my summers growing up in a small village in the Vosges mountains in Alsace, not far from where my grandfather was born and his relatives before him.

Up the road from the 200-year-old house where we came every year was a small opening. It didn’t look like much, a little break between the houses, but if you climbed up the hill, there was a path where the trees met overhead, a Narnian gateway to my favorite place in the world: the forest, a wonderland of tall green creatures, beds of fern and countless wild strawberries.

The Christmas tree brings me back to that forest of my childhood. It reminds me that the true magic of the season – for me, more pagan than Christian – lies outside, in the dark woods where the trees wait for spring. And it reminds me that our survival – now, more than ever – depends on the natural world and, most particularly, forests.

What about that question I began with? How should we feel about bringing a cut tree into our homes, even if its not taken from a functional forest? I confess I did have a cut tree this year, but, in the future, I may consider one of the eco-friendly alternatives that are becoming more common. In some places, you can rent a live tree or you can buy one to plant somewhere after the Christmas season is over. If you do have a cut tree, it’s important to think about what will happen to it when it leaves your home. In my village, trees are mulched for further use, but Christmas trees can continue to give of their lives in other ways as well.

In gratitude for what trees give us, we can also use this season as an opportunity to find ways to give back to the forest – by volunteering in a local park or nature preserve or by donating to one of the many organizations that help protects forests throughout the world. This year, I gave to this one and this one.

3 comments on “Christmas Tree”

Comments are closed.

Lovely description. I have had years where I, too, felt particular poignancy over celebrating around a now dead tree. Most years I just enjoy it, as such sensitivities in the flurry of life do tend to wax and wane. And I am moved, too, by this new bit of history as a whole branch of my ancestors also hail from Alsace, and my mother vividly remembers her Alsatian grandmother insisting on lighting the tree only on Christmas Eve, with candles.

Early on in my first child’s life I felt mildly troubled by whether or not I needed to explain the Christian tradition of Christmas in our long-not-Christian family. But I too read up on it’s origins and as we’ve always celebrated the solstice in my family I decided that it could be a holiday about lights, the returning light, family and traditional foods, some passed down from that same great grandmother, and eaten on her china (the kids don’t forget presents). Certainly Santa Claus is not a Christian figure, although his roots are rather dark, so we pass those stories by.

My childhood, while not itinerate, was marked by every summer spent with my grandparents on their farm in rural Pennsylvania. And for me and my brother, the forrest was always the most magical place. It was so dense it was dark, and fragrant, and held the promise of berries and the promise/ exciting threat of bears. There was a spot in the middle where there was a clearing, but one could not reach it because the thick vines were three layers deep. In there the fairies lived. We maintained this until quite old ages, because the entire place meant magic to us.

Tree planting has always been a big part of my life and I, too, hope that families create that tradition for the next generation.

Thanks Nicole!

Thank you for the article, Nicole!

When you mentioned Christmas origins …three cultural influences: Roman pagan, folk pagan and Christian…you awakened my curiosity again; how many elements from the Christmas traditions I grew up with coming from those old old times, or may be even from the origins… I’m Lithuanian (the last pagan country in Europe) and despite being years under different suppressive systems, we, Lithuanians, carried out our precious folkloric rituals, games, traditions for Christmas eve and day, what apparently was “nurtured” from pagan times. And yes, the forest is and always was a sacred place and “cutting down a sacred tree was a very unattractive job”…

Thanks again,

I would love to hear more about your experience!