When I walked my daughter to school today, it was cold, there was a hard wind and a number of things to grumble about. She needed some distracting. Luckily, we saw some hawks who have been circling over an area of our Village near the elementary school and an adjacent church. I drew her eye and her thoughts to the hawks. “I wonder why they’re gathering here?” I said.

My daughter, who had already been observing the hawks at recess, didn’t hesitate for a moment: “They’re visiting their cousins,” she told me, as if this were self-evident, and proceeded into further details of the family reunion. They were offering gifts to each other – leaves for the little ones. “Do the little hawks like to play with acorns?” I asked. “Yes, they spin them like dreidels.” And, in a burst of creative glee, she found the theme: “Hawknukkah!”

Ah, there was some material! What would the menorah be? A branch perhaps with stars for lights? And on we went.

As I walked back home after leaving my daughter at school, warmed by the story we had kindled and by the presence of the hawks, I thought about how naturally children relate to plants and animals. I thought about the kinship they feel with them and the stories they concoct of all they see. And I thought about the stories that shape us as children. An important one for me was The Wind in the Willows. My grandmother grew up near Kenneth Grahame and knew him as a child and she read the book out loud to me, in person and on tape, so I could listen to it over and over.

Let’s take a moment to read a passage from the first chapter, when Mole encounters a river for the first time:

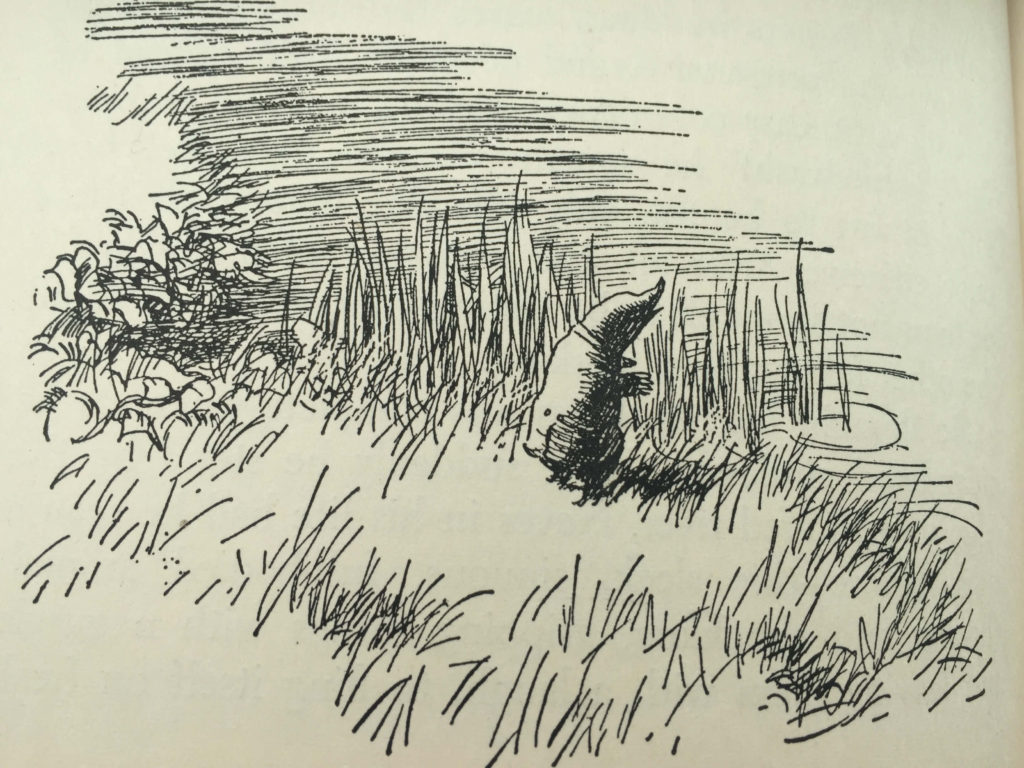

He thought his happiness was complete when, as he meandered aimlessly along, suddenly he stood by the edge of a full-fed river. Never in his life had he seen a river before – this sleek, sinuous, full-bodied animal, chasing and chuckling, gripping things with a gurgle and leaving them with a laugh, to fling itself on fresh playmates that shook themselves free, and were caught and held again. All was a-shack and a-shiver – glints and gleams and sparkles, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble. The Mole was bewitched, entranced, fascinated. By the side of the river he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spellbound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.

What better ambassador to the wonders of a river than Mole, whose small stature gives us the close-up view that Grahame likens to that of a child, bewitched by the best of storytellers. There is plenty that could be said about the ways in which Grahame conveys the life and subjectivity of Mole and the river in this scene. How lovely, for example, that he doesn’t use human names for his characters: the capital “M” of a proper noun does the job much better. And, to the river, he gives life with a veritable stream of verbs.

Whenever people write about animism in its various forms, they feel compelled to distinguish it from anthropomorphism (or to condemn it as such), anthropomorphism being one of the cardinal sins of the scientist and the social scientist. We all know the shortcomings of projecting human feeling, human motivations, human behaviors onto other creatures. And, yet, as children remind us, it’s a natural impulse.

As I ruminated this morning on children’s stories – those they read and those they tell – I wondered if we shouldn’t be a bit more forgiving of our tendency to project our own thoughts and feelings onto the natural world. Certainly, there is plenty to be said about the virtue of being open to the other, to what is unknown and unknowable. But our ability to map our own feelings and experiences onto other living beings is also an expression of empathy and isn’t empathy the gateway to all loving relationships?

Looking back at the passage of The Wind in the Willows, I also wonder if anthropomorphism can’t be a conduit to a deeper understanding, especially if it means being attentive observers as well. When Grahame describes the river as “chasing” and “gripping” and catching its “playmates,” a scientist might tell you that this is because of water’s adhesion to other surfaces: the attraction of its negatively-charged hydrogen molecules to the positively-charged molecules of other substances. Conversely, the river is a “full-bodied animal” because of its cohesion: the attraction between its own hydrogen and oxygen molecules.

The scientist’s lesson and Grahame’s prose, these are different ways of knowing and, certainly, in our relationship to the natural world, we need many different ways of knowing. Perhaps, just as importantly, we need different ways of coming to know, human to Mole, Mole to river and girl to hawk.