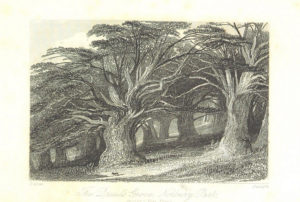

“The Druid’s Grove, Norbury Park”

illustration from A hand-book of Dorking, second edition, John Dennis, 1858

The British Library

In an earlier post, I wrote about a kind of literacy we seem to have lost: the ability to “read” our landscape, to recognize and name the plants that make up our natural world.

Thinking about this analogy between nature and writing, I started to wonder if one kind of literacy supplants another. In other words, does the advent of writing – and reading – affect our ability to recognize and interpret the natural world?

One of the things that brought this question to mind was something I read about the Celts. I’ve been fascinated by these ancient peoples of Europe ever since I studied Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, which opens with a rather evocative conjuring of the narrator’s “barbarian” ancestors.* When I started reading about these “Gauls” or Celts, I discovered, to my delight, that they had a number of things in common with Native Americans, including a propensity to tattoo their bodies and an intimate knowledge of plants.

Like the Native Americans, the Celts were largely wiped out by invading forces who did their best to annihilate them culturally – moreover, we know very little about their life and culture because they did not leave a written record. (Instead, historians must rely on the accounts of Greeks and Romans, on what they can piece together from the archeological record and on later transcriptions of oral history.)

According to Julius Caesar, this absence of writing is not an accident: the druids forbade any of their teachings to be put in writing. Caesar speculates that this prohibition had two motives: to develop the memories of their initiates, who would train, memorizing verses, for up to twenty years, and to protect their knowledge from falling into the wrong hands.

This begs the question of what exactly they were protecting. I found an interesting theory in an article published by the religious studies scholar Georges Dumézil in 1940, entitled (I’m translating) “The druidic tradition and writing: the living and the dead.”

Dumézil links the Celts to other religious traditions that also “resisted the temptation of writing” (127). What is there to resist? A series of pitfalls as he sees it:

The risks of writing […] are the risks of false application, of non-discernment […] to begin with, of course, the risk of divulging [information to those who can’t understand], the risk of being misunderstood, poorly explained or having the meaning be misconstrued, altered (conflict between the letter and the spirit of the law), the risk of being catastrophically misapplied (as in the case of a magic potion for instance), the risk of falsification […] perhaps most of all, in the long run and, in any case, the risk of aging, of wear and tear, of ceasing to have the same meaning (expressions no longer being properly understood and becoming pure fossils, rendered dead by the very means that was meant to preserve them) (128-129).

In short, spoken language is living language. It is intricately tied to a time and a place. When it travels in written form, it finds a home in a new situation where it might easily be misused or misunderstood. In the age of “fake news” and bots, it’s not hard to understand what he means. Indeed, writing in its new forms seems to have opened up a veritable chasm between language and truth.

Dumézil also emphasizes the uses to which the druid’s verses would be put. Take for instance the “magic recipe” (I translated it as a “magic potion” above, but I was taking poetic license.) Imagine for a moment the gestures, the touching of plants, the measuring and mixing that would accompany the incantation. This example gives us a good idea of the risk of misinterpretation: get the recipe wrong and it might turn deadly.

This picture of language as embedded in actions, in a time and a place, brings us back to the question of the relationship between language and the natural world. The natural world is of course, like this living language, a living world, in constant flux. (By contrast, we find written language, fittingly, on the reconstituted pulp of dead trees.) Our ability to interpret it, to respond to it is all highly contextual – it depends on the time of year, the weather, who’s there, what’s happening. Moreover, our engagement with the natural world, our ability to “read” it, is tied to our actions. To “read” the natural world is to navigate it; to recognize the plants that are good for eating; those that are good for medicine or tools or for building shelter; to stay clear of those that sting or poison; to recognize the passage of deer, of wolf, of possum; to feel a change in the weather… In other words, meaning is inextricable from action, from an engagement with our surroundings. It becomes easy then to see how writing, which can at best serve as a transcription of such warm-blooded action, is an estrangement from this enmeshment with a breathing, moving world.

And then of course, as I sit here at my desk, peering through the window at the leaves blowing about in the wind, I’m reminded of the obvious way in which writing removes us from the natural world. The distance is at once physical and mental – I reconstitute the world in my mind and then, again, in my writing.

But the truth is it seems virtually impossible to imagine what it was like to live in a world without writing. Though I suppose we have our modern analogies: I do remember what it was like to live without cell phones. Is there something we could recover from a world without writing the way that, for example, I want my children to navigate the world without cell phones before they are permanently tethered to this technology? I guess to find out I would have to go on one of those retreats, off-grid, without (gasp) books. The idea is at once terrifying and exhilarating: like dangling over the edge of the unknown.

*From my ancestors the Gauls, I have blue-white eyes, a narrow skull, and awkwardness in fighting. I find my clothing as barbaric as theirs. But I do not butter my hair.