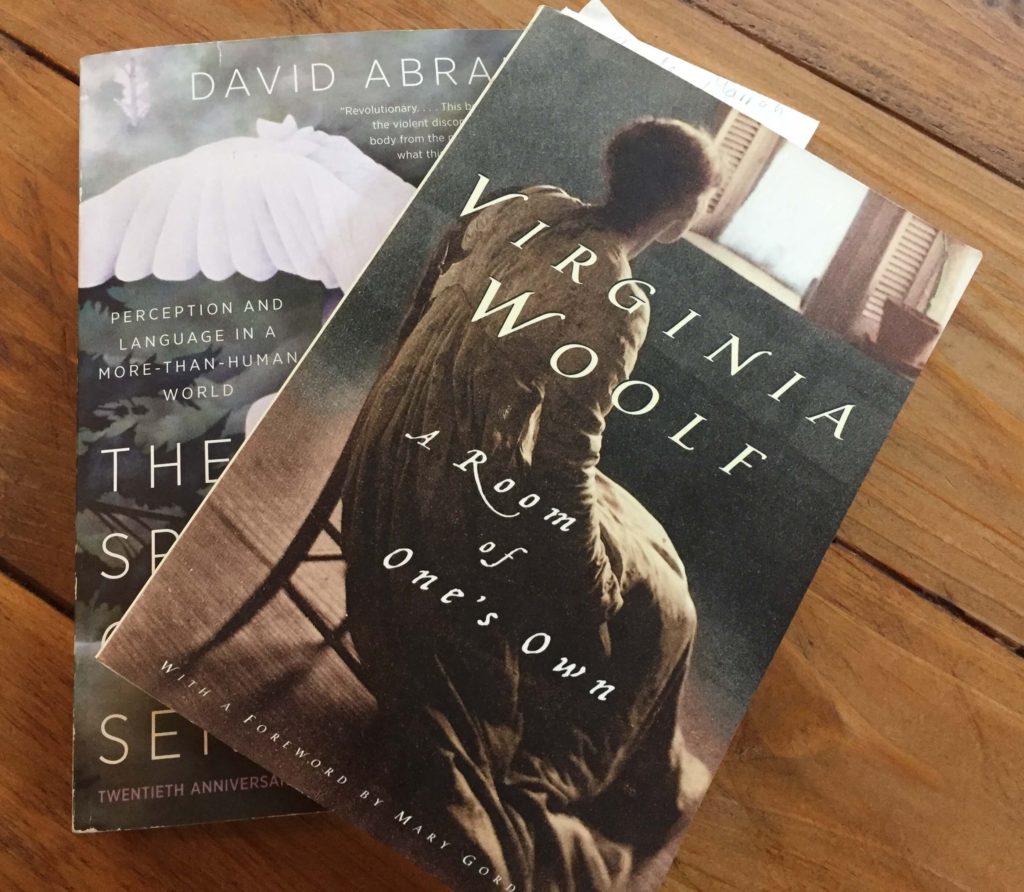

The book that has been waiting for me in the wings – ecologists and philosophers could have told me – is David Abram’s The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than Human World.

It’s been a classic of the environmental movement for over twenty years but is new to me. Abrams speaks to many of the subjects I’ve already written about in this journal but also to earlier preoccupations of mine, going back to my days as a student of poetry – but more on that later.

Perhaps most dramatically, Spell explores the connection between writing and our relationship with the natural world that I touched on in my musings on the Celts. In answer to my question, “Does Writing Remove Us?” Abram offers a rich reply: our relationship with the natural world was fundamentally altered by the invention of writing, he argues, especially after the phonetic Greek alphabet that came fully into use around the time Plato was cleaving the world of ideas from the world of experience.

The book opens with an account of Abram’s experience doing research among shamans in Indonesia. When he returns to the U.S., he realizes how profoundly we in the West are cut off from the sensory experience of the world we inhabit:

Caught up in a mass of abstractions, our attention hypnotized by a host of human-made technologies that only reflect us back to ourselves, it is all too easy for us to forget our carnal inheritance in a more-than-human matrix of sensations and sensibilities. (22)

To make sense of this disconnect, Abram turns to phenomenology and, in particular, the work of the French thinker Merleau-Ponty, for whom, contrary to the view we’ve inherited from Descartes that the thinking mind is distinct from the material world, knowledge is necessarily grounded in our subjective, lived experience. Borrowing Husserl’s term “life-world” (Lebenswelt) Abram argues that we come to know the world through a multi-sensory (in fact synesthetic) participatory relationship with all other beings, human and Other.

The phenomenologist, properly tuned to the fundamentally subjective, embodied nature of human knowledge, experiences the world as profoundly alive. Abram argues that – as evidenced by indigenous cultures around the world – humans start from an animistic understanding of the world: other animals, plants, stones, streams are encountered as subjects, perceiving us as we perceive them.

It’s important to note, however, that when Abram talks of the world as animate, we should not mistake this for a form of spiritualism. In fact, he thinks that anthropologists have misinterpreted many indigenous cultural practices as having to do with spirits, in the Western sense of a spirit as non-physical, falsely attributing modern religious or philosophical concepts to cultures in which no such distinction between the spirit world and physical world exists.

If we follow Abram, then, it’s clear that something had to happen for humans to experience themselves as apart, unique, different. In his narrative – and he acknowledges that this is only one way to tell the story – this separation happened when we transitioned from oral to written culture.

Abram sees oral cultural as an extension of our embodied, participatory relationship with the world. Think of it this way: until the invention of recording devises, speech could not be separated out from our bodies or the physical world we inhabited. All speech was situated, its meaning could not be disentangled from the context in which the words were spoken, from tone, the actors and actions to which they were tied. Human language thus participated in the resonant world in which many creatures make meaningful sounds – from howling wolves to chirping squirrels to the rain sliding down the gutters as I write.

Something shifted with the emergence of the written text, especially after the advent of a phonetic alphabet that, unlike the pictographic marks of ancient Chinese and other earlier writing systems, no longer pointed to the world outside of human-made meaning. (Abram’s account of the invention of writing systems is quite gripping.)

For Abram, it is more than a coincidence that the Greek alphabet comes into common use around the time that Plato was laying out his theory of ideas. Indeed, Plato “and his mostly non-literate teacher Socrates” are the “hinge on which the sensuous, mimetic, profoundly embodied style of consciousness proper to orality gave way to the more detached, abstract mode of thinking engendered by alphabetic literacy.” (109)

The result is a kind of hall of mirrors: we transfer the animating magic of the world onto writing itself, a closed system of human-generated meaning, sealing ourselves off from communion with other beings: “the trees become mute, the other animals dumb” (131).

I feel the need to breathe here. It’s a lot to take in.

Abram concludes, not by rejecting writing, but with an injunction to knit the original magic back into our writing. As he describes what he means, his prose turns poetic:

Our task […] is that of taking up the written word, with all of its potency, and patiently, carefully, writing language back into the land. Our craft is that of releasing the budded, earthly intelligence of our words, freeing them to respond to the speech of the things themselves – to the green uttering-forth of leaves from the spring branches.[…] Finding phrases that place us in contact with the trembling neck-muscles of a deer holding its antlers high as it swims toward the mainland, or with the ant dragging a scavenged rice-grain through the grasses. Planting words, like seeds, under rocks and fallen logs – letting language take root, once again, in the earthen silence of shadow and bone and leaf. (273)

This shift towards a more poetic style isn’t an accident. Poetry creates a kind of opening for Abram. It hearkens back to oral traditions: meter, rhyme are the tricks of the trade when all that text needs to be learned by heart.

As Abram points out, there is also a fundamentally different conception of time at work in poetry than in prose. It’s in the words themselves: prose, etymologically, means to move forward, straight ahead, whereas, verse, from the Indo-European “wer,” to bend, involves a turning, as in the turn of a plow.

If poetry is the stuff of Homer and other oral traditions, prose is a child of the written word: as Abram points out, early Greek historians pioneered the use of prose in texts that exemplified the modern conception of linear time (198), whereas poetry, in form as well as function, has its roots in a pre-modern cyclical conception of time.

But there’s something else. In poetry, the musicality of language is an essential part of the way that it produces meaning, that aspect of spoken language Abram refers to as the “tonal, melodic layer of communication […] – a rippling rise and fall of the voices in a sort of musical duet, rather like two birds singing to each other” (80).

This last sentence – a description of two people talking – reminded me of a passage from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own that has haunted me over the years.

In the opening section of A Room of One’s Own, Woolf imagines a fictional version of herself at a luncheon in “Oxbridge.” After the exquisite food (“We are all going to heaven and Vandyck is of the company”), she sits down at the window-seat to smoke a cigarette. Everything has conspired to make this a truly lovely moment until something jars her: the sight of a cat without a tail. It’s like a fly in the ointment, a wrench in the…. whatever. It makes her realize that something isn’t quite right and that not quite rightness, she realizes, is a quality in the conversation that surrounds her. Not the words, but the melody.

What is it? What’s wrong? She turns to two poets, Tennyson and Christina Rossetti, whose romantic lyricism conjures the “humming” of men and women before the war (she means World War I), a melody that is absent in the intercourse of those around her now. The poetry bewitches her (and her readers too):

There has fallen a splendid tear

From the passion-flower at the gate.

She is coming, my dove, my dear;

She is coming, my life, my fate;

The red rose cries, “She is near, she is near”;

And the white rose weeps, “She is late”;

The Larkspur listens, “I hear, I hear”;

And the lily whispers, “I wait.”

And Rosetti’s reply:

My heart is like a singing bird

Whose nest is in a water’d shoot

My heart is like an apple tree

Whose boughs are bent with thick-set fruit;

My heart is like a rainbow shell

That paddles in a halcyon sea;

My heart is gladder than all these

Because my love is come to me.

Significantly, Woolf leaves the mystery of this disjunction between past and present unresolved, but there’s the sense that the war has, in some way, irreparably damaged people’s ability to connect with each other; the cat’s truncated tail of course stands in for this violence, bringing to mind the amputations suffered by soldiers.

Woolf sees that poets express something that is happening in our language that we are not aware of ourselves, that we can only recognize in hindsight. The “humming” of Tennyson and Rosseti’s poetry stands in for the dimension of language that resonates beyond and, perhaps, even, in spite of the meaning of the words themselves. At the two luncheon parties Woolf imagines – one before the war and one after – the small talk is the same but the effect of the conversation is fundamentally different.

In her ingenious way, Woolf reminds us that language is fundamentally social, that it is a way of acting in relation to others. In our modern world, this may mean predominately other humans – we may no longer speak to trees and stones as our ancestors did – and yet can we really be in conversation with each other without, in some way, feeling the world around us? It seems telling to me that Tennyson and Rossetti – as poets frequently do – convey love through elements taken from the natural world. “My heart is like a singing bird” and “She is coming my dove, my dear.” Birds singing to each other indeed.

I’m not sure that language – even written language – can ever be fully contained within its own prism. Language is necessarily of the stuff of the world and the ways in which it testifies to our place in the world – our social class, say, our education, our temperament – has a way of leaking out. Language is part of the bloody encounter of beings, in love and violence, peace and war.

I’ll be honest. I don’t quite know how to close this entry. There’s so much more to say, to learn, to hazard. So let’s make this a “to be continued.”